Chapter 25: The 'Negative' Stellar Parallax demystified

The concept of parallax is fairly simple : it is the effect of (apparent) lateral displacement of a nearby object in relation to a more distant one - as you are moving past the two objects. For instance, imagine driving down a highway in your car and looking at the scenery through your righthand window. As you drive by a nearby tree, it will seem to drift from left to right in relation to the background scenery. Of course, the tree is not moving in relation to the background scenery - it is just an optical effect caused by your own motion. Similarly, stellar parallax deals with the (apparent) displacement of a nearby star in relation to more distant stars. As Earth moves along, nearby stars can be seen to move (by extremely small, 'microscopical' amounts) in relation to far more distant stars, a.k.a. the "fixed stars" (in astronomy jargon).

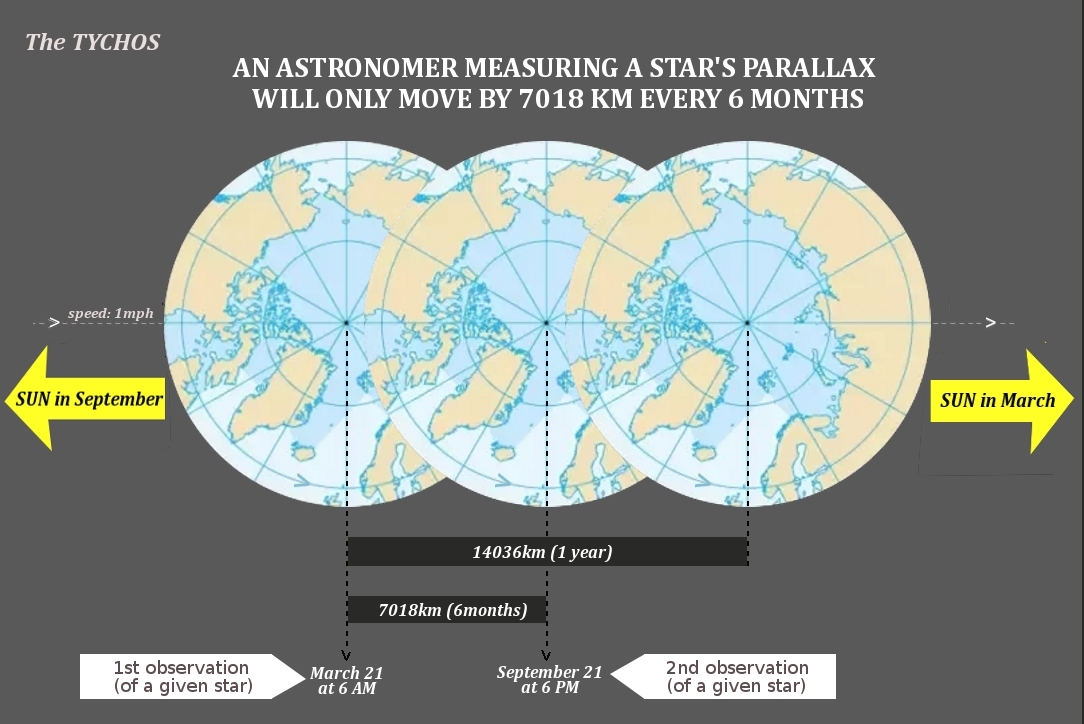

Since Copernican astronomers believe that our planet orbits around the Sun around a 300 million-km-wide circle (as we saw in Chapter 23), they will take two measurements - of any given nearby star - separated by a 6-month period. This, because according to their reasoning, the Earth will then have moved from one side of its orbit to the other and thus, must have displaced itself by its maximum elongation in relation to the stars. As they compare the two observations of that star, they will calculate its parallax trigonometrically - using a baseline of 300 Mkm... In the TYCHOS however, the Earth only moves by a mere 7018km every six months. This is of course a quite small displacement with respect to the distant stars which, in fact, helps explain why detecting stellar parallaxes was impossible in Tycho Brahe's times - and is still a formidable challenge for our modern-day astronomers:

Before we get on, an important point concerning the history of stellar parallax measurements needs to be clarified:

“It is important to notice that the early attempts were at measuring what today would be called absolute parallax, rather than relative parallax, which is the parallax of a nearer star with respect to that of a distant star”. "The Historical Search for Stellar Parallax" - by J. D. Fernie, from Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (1975)

As it is, for a few centuries following the onset of the so-called "Copernican Revolution", the failure to detect any relative stellar parallax (by our world's top astronomers) remained a critical problem for the Copernican heliocentric theory. It was logically thought that, if Earth travels around a 300 million-km-wide orbit around the Sun, at least some relative stellar parallax had to be detectable. Yet, it wasn't until 1838 that Bessel detected some minuscule parallax for star "61 Cygni" (a confirmed binary system). Bessel's observation was then triumphantly hailed as a robust confirmation of the Copernican postulate that Earth revolves around the Sun...

Today, the two major, official stellar parallax catalogues - named "Hipparcos" and "Tycho" - published by ESA (the European Space Agency) contain the parallax values for a few million stars. Indeed, ESA now proudly proclaims that their current "Gaia" enterprise will soon determine the parallaxes / celestial positions & distances for a billion stars.

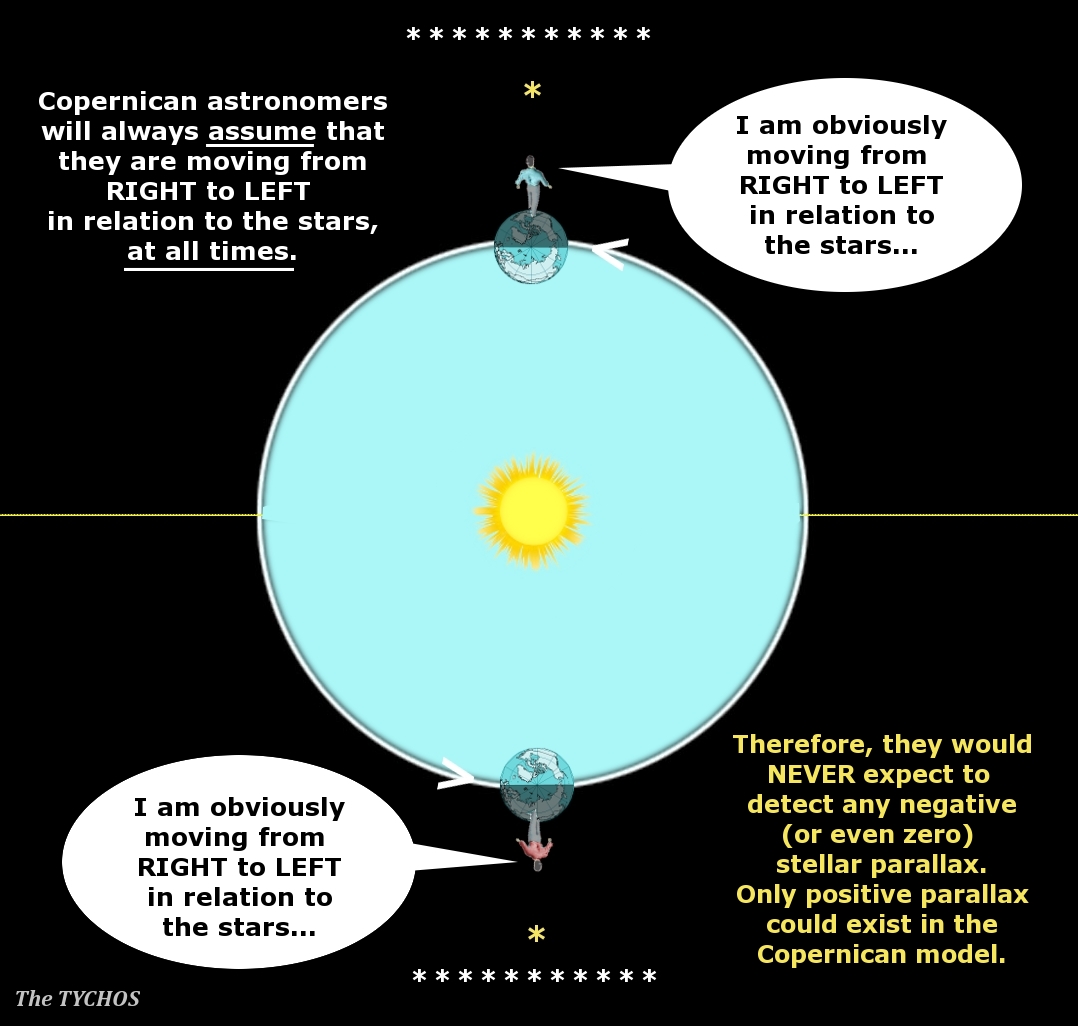

Now, here is the problem: in later years, a number of independent researchers have pointed out some seemingly inexplicable aberrations, as they patiently scoured ESA's largest database (their curiously-named "Tycho" catalogue of about 2 million stars): they have found that roughly 25% of the stellar parallaxes are "negative", 29% are "positive" - and 46% are "assumed zero" (i.e. almost HALF of the stars listed in the Tycho catalogue exhibit NO observable parallax at all !). To illustrate why the so-called "negative stellar parallax" would be, under the Copernican model's geometry, an utter aberration, I have made the below graphic.

Imagine yourself travelling in a car orbiting around the Sun (as Earth supposedly does according to Copernican theory). As you look out from your lefthand window, you will see the Sun - at all times (let's assume - for the sake of simplicity - that the car doesn't spin around itself every 24 hours). In order to SEE any stars, you will have to look out of your righthand window - at all times. Therefore, if you were to measure any stellar parallax (of relatively nearby stars - against more distant ones), only "positive" parallax could possibly be observed - at all times. In other words, the nearby stars will ALWAYS seem to move from left to right (or from east to west) in relation to the more distant background stars. Here's a conceptual graphic illustrating this indisputable fact:

Yet, about 1/4 (or 25%) of all the stellar parallaxes listed in ESA's Tycho catalogue have negative values, essentially meaning that they were observed to move from right to left (or from west to east) in relation to the more distant background stars. How can this possibly be?

Well, we shall now see why the TYCHOS model provides the simplest & most logical resolution imaginable to this most troublesome affair. In short, since Earth slowly orbits within the Sun's orbit, stars will actually be observable out of BOTH the "lefthand and righthand windows of your car"! Therefore, the distribution of stellar parallaxes will be fully EXPECTED to be as they are, in fact, being observed: i.e. roughly 25% "positive" and 25% "negative"; whereas the remaining 50% of "zero parallaxes" will be evenly distributed in your front and rear car windows - and this, because no parallax (of any nearby star) can be detected whilst you are driving either towards or away from the stars in your field of view. Before proceeding, however, we should first take a brief look at the history and basics of stellar parallax detection. Let's start with this short extract, courtesy of the Astrosociety.org website:

“Hipparchus of Nicaea (2nd century BC) is the first known astronomer to have made careful observations and compared them with those of earlier astronomers to conclude that the fixed stars appear to be moving slowly in the same general direction as the Sun. Confirmed by Ptolemy (2nd century AD), this understanding became common in medieval Europe and the Near East, although a few astronomers believed that the motion periodically reversed itself.”

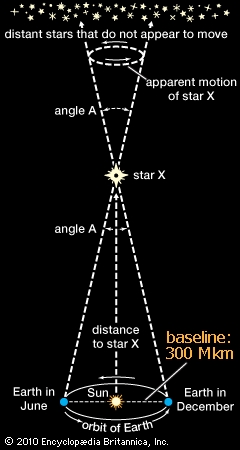

Copernican astronomers measure the distance to the stars as follows. They look at a given, nearby star “X” and record its position against far more distant stars (a.k.a. the "fixed stars"). Six months later, they look at star “X” again and, if it has moved by any amount in relation to the fixed stars, they call this apparent displacement the parallax of star X. Why six months? Well, Copernican astronomers assume that, in six months, Earth has changed positions by about 300 Million km, from one side of its orbit to the other. Therefore, they assume that these recordings represent the baseline upon which they can perform a simple trigonometric calculation to determine the stars’ distances from Earth. Of course, this reasoning is based upon the idea that Earth revolves around the Sun. Here's from the Encyclopædia Britannica entry on "Techniques of Astronomy":

“The annual parallax is the tiny back-and-forth shift in the direction of a relatively nearby star, with respect to more-distant background stars, caused by the fact that Earth changes its vantage point over the course of a year. Since the acceptance of Copernicus’s moving Earth, astronomers had known that stellar parallax must exist. But the effect is so small (because the diameter of Earth’s orbit is tiny compared with the distance of even the nearest stars) that it had resisted all efforts at detection.”

"The techniques of astronomy" - by James Evans (2017)

Following the invention of the telescope, and for a very long time, no astronomers were able to detect any amount of stellar parallax. Only as late as 1838 did Friedrich Bessel triumphantly announce to have observed the parallax of 61 Cygni (a binary pair - and the 7th nearmost star system).

“At the end of 1838, Bessel announced that over a period of one year 61 Cygni made a small ellipse in the sky. The greatest displacement from the average position was just 0.31” with an error of 0.02”. This tiny motion of 61 Cygni was a direct consequence of Earth’s motion around the Sun. Bessel had finally discovered an annual parallax.”

— "Measuring the Universe: The Cosmological Distance Ladder" - by Stephen Webb (1999)

Of course, according to the TYCHOS model, what Bessel saw was not a consequence of the Earth’s motion around the Sun, but of the parallax caused by our small 7018-km-six-month displacement in relation to star 61 Cygni and the fixed stars. Yet, Bessel’s microscopic parallax detection of our 7th nearmost star system was widely celebrated as "conclusive proof of Earth’s motion around the Sun"!

As mentioned earlier, Copernican astronomers will obviously assume that Earth always moves in the same direction in relation to all the stars. Therefore, they will expect any stellar parallax shift (between the closer and more distant, 'fixed' stars) to exhibit what is known as positive parallax, exclusively and at all times, since Earth’s motion around the Sun is certainly not believed to ever reverse direction! This is why "negative" stellar parallax constitutes a physical impossibility within the heliocentric paradigm - and an utterly insurmountable problem.

Above: A graphic from the Encyclopædia Britannica entry on “Parallax”.

Below: My graphic showing why negative stellar parallax simply cannot exist in the Copernican model.

As a matter of fact, it has been known for centuries that astronomers have kept detecting nearby stars exhibiting negative parallax. In other words, nearby stars have regularly been observed to drift in the opposite direction the Copernican model predicts. Strangely, there is practically nothing to be found regarding this very serious problem in modern astronomy literature. The question of negative stellar parallaxes appears to be a 'taboo topic' among today's astronomers - yet it is one which has eluded any rational explanation to this day. Back in 1878, the famous astronomer Simon Newcomb briefly commented on this thorny issue, suggesting that “such a paradoxical result can arise only from errors of observation”.

Perhaps the most ironic "twist" of the entire history of stellar parallax detection - and as very few will know - is the fact that Bessel (the man credited for making the first "indisputable stellar parallax determination that finally proved Earth's motion around the Sun"), INITIALLY detected and reported a number of negative star parallaxes! And not only for the star 61Cygni, but also for Cassiopeaie - while Sir James Bradley had even observed negative parallax for our very North Star, Polaris! Here's an extract from one of the more inquisitive, fact-filled books by earnest astronomy historians that I have devoured over the years:

"But Bessel was to be disappointed again: when he had finished the reduction of the position of 61 Cygni relative to the six different stars he was forced to the conclusion that its parallax was negative! The paper in which this result was announced took the form of a report only, with no explanation of why a negative answer might have been obtained. Bessel gave tables of observations, and results of the application of the method of least squares to these observations for each comparison in turn; he followed this with exactly the same information for μ Cassiopeiae which he had compared with θ Cassiopeiae. For this star also he had a negative, though numerically smaller result. In volume III of the Konigsberg observations Bessel gave another set of observations, this time of the difference of right ascension between α and 61 Cygni from which he deduced an even larger negative result for the parallax of 61 Cygni. A different account may be constructed from Bessel's private correspondence. In a letter to Olbers written at about the time that the first set of negative results for 61 Cygni was published, Bessel stated that: "The negative parallax which one found here and there and which he had in fact found for the Pole Star from Bradley's observations was of course the result of observational errors".

"Attempts to measure annual stellar parallax-Hooke to Bessel" - by Mari Elen Wyn Williams (1981)

Before proceeding any further, you should know that the entire history of stellar motion measurements reads like an almost kafkaesque novel of dire, tragicomical confusion. Since virtually all of the most acclaimed astronomers of recent centuries were 'Copernican disciples', they simply had no chance to make any sense of their own (starkly conflicting) stellar parallax measurements. As they compared the data of their various star observations (all performed during different annual time windows), they couldn't even agree on the actual DIRECTION of any given star's proper motion! (A star's "proper motion" simply refers to its own peculiar displacement in space - in any given "x-y-z" direction in Euclidian space). Sir Francis Baily was a major figure in the early history of the Royal Astronomical Society, as one of the founders (and four-time president) of the same. Here's what Sir Baily had to say about this most embarrassing state of affairs:

"For, in many cases, some of the greatest names have differed even as to the direction of the motion of particular stars : one making it positive whilst in the same star another considers it as negative."

In a footnote of his Catalogue of Stars (linked below), Sir Francis Baily mentions the befuddling case concerning the parallax measurements of 10 stars by Baron Zach and Nevil Maskelyne: the former reported positive parallaxes for them all, whereas the latter reported negative parallaxes for them all!

But let us get on - and take a look at a few other scientific papers specifically concerned with stellar parallax. Here are two extracts from Eichelberger's paper (published in the famed 'SCIENCE' journal on April 7, 1916) titled "THE DISTANCES OF THE HEAVENLY BODIES":

So let's see: if only "somewhat more than half" of those 245 stars had a measurable parallax, this means that somewhat less than one half (shall we say about 120?) exhibited "zero" - or undetectable - parallax. Of the other "more than half" (shall we say, 125?), as many as 54 exhibited negative parallax!

In this other paper published in the ASTRONOMICAL JOURNAL (1912) titled "Results for parallax from meridian transits at the Washburn Observatory", we may find this table showing that the proportion of observed positive versus negative stellar parallaxes was roughly 50:50 :

You may now ask: "what about more recent observations? Hasn't technology progressed since the early 19th century"? Of course it has - good point! So let's take a look at this paper from 1966, titled "THE ACCURACY OF TRIGONOMETRIC PARALLAXES OF STARS" - by Stan Vasilevskis (of the famous Lick observatory). In this paper, Vasilevskis reports how the four major American observatories were puzzled and bewildered by the disturbing differences, discrepancies and disagreements between their respective, meticulously-gathered stellar parallax data:

"Parallaxes of the same stars determined by different observers and instruments often disagreed to such an extent that the reality of some parallaxes were in doubt. Although the homogeneity has high statistical merit, the absence of various approaches makes it difficult to investigate and explain discrepancies between various determinations of parallaxes for the same stars. There are disturbing differences, and many investigations to be reviewed later have been carried out on these discrepancies. The present paper is a review of the present material, and a consideration of the possibilities of modifications in the technique of parallax determination in view of past experience and the present status of technology."

"THE ACCURACY OF TRIGONOMETRIC PARALLAXES OF STARS" - by S. Vasilevskis (1966)

So, as recently as 1966, the four major American Observatories were mystified as to the "disturbing discrepancies" between their respective stellar parallax measurements - to the point that "the reality of some parallaxes were in doubt". Curious, isn't it? But let's now fast-forward to our present times. As every modern-day astronomer knows, ESA (the European Space Agency) proudly boasts about the purported pinpoint accuracy of their star catalogues, which they claim were compiled with data collected by their orbiting space-telescope installed aboard the “HIPPARCOS” satellite (and still more recently, with its latest $1 billion "GAIA satellite" project).

"Observationally, the objective was to provide the positions, parallaxes, and annual proper motions for some 100,000 stars with an unprecedented accuracy of 0.002 arcseconds, a target in practice eventually surpassed by a factor of two."

The HIPPARCOS satellite - as depicted at this nasa.gov webpage

The HIPPARCOS satellite - as depicted at this nasa.gov webpage

“The Hipparcos and Tycho Catalogues are the primary products of ESA’s (the European Space Agency’s) astrometric mission, Hipparcos. The satellite, which operated for four years, returned high quality scientific data from November 1989 to March 1993.”

— "The Hipparcos and Tycho Catalogues" - ESA (1997)

In later years, a number of independent researchers have profoundly questioned the catalogues of stellar parallax data released by ESA, allegedly collected with a midget 29cm telescope mounted on a tinfoil-hatted, remote-controlled satellite circling the Earth at hypersonic speeds, around an eccentric orbit ranging from 500km (perigee) to 36000km (apogee)! We mere mortals can only wonder just how that's supposed to work, but the more fundamental question is: since stellar parallaxes are, by definition, microscopic perspective shifts between closer and more distant stars AS VIEWED FROM EARTH, what purpose would it serve to collect such data from a spacecraft hurtling at breakneck speeds around some highly eccentric orbit around our planet? Only ESA knows, I presume. In any case, the Hipparcos was acclaimed (by ESA) as a "roaring success", what with their claimed accuracy of stellar parallax data of 0.001 arcseconds (i.e. 1 milliarcsecond!). Quite some feat, you might say - but most astronomers seem to buy it.

Anyhow, whether such extraordinary claims are true or not, the most interesting fact is that ESA's largest stellar parallax catalogue (named, oddly enough, the "TYCHO catalogue") which lists the parallax data for more than 2 million stars, contains about 1 million NEGATIVE parallaxes! This was noticed several years ago by a distinguished Italian astronomer, Vittorio Goretti - who passed away in 2016 (unfortunately, I only came by his work in 2017). In the last years of his life, Goretti vigorously demanded clarifications from ESA regarding this glaring absurdity. As so often is the case with folks questioning ESA and NASA (a.k.a. "Never A Straight Answer") his demands were met with deafening silence. Goretti pointed out that:

“As a matter of fact, about half the average values of the parallax angles in the Tycho Catalogue turn out to be negative! The parallax angle, which is one of the angles of a triangle,is positive by definition.”

Aside from the negative parallaxes, Goretti also had some serious questions concerning ESA's evident cherry-picking of the stars / and stellar parallax data selected for publication in their far smaller HIPPARCOS "show-case" catalogue (containing only about 118000 stars) which they claimed was "more accurate than the larger TYCHO catalogue - and thus contained far fewer negative star parallaxes". He also questioned how the HIPPARCOS' small 29cm telescope could possibly have achieved such formidable accuracy (+/- 1 milliarcsecond) as advertised by ESA. Here's an extract from Goretti's website:

“The Hipparcos Catalogue stars, about 118,000 stars, are a choice from the over 2,000,000 stars of the Tycho Catalogue. As regards the data concerning the same stars, the main difference between the two catalogues lies in the measurement errors, which in the Hipparcos Catalogue are smaller by about fifty times. I cannot understand how it was possible to have such small errors (i. e. uncertainties of the order of one milliarcsecond) when the typical error of a telescope with a diameter of 20÷25 cm is comprised between 20 and 80 milliarcseconds (see the Tycho Catalogue). When averaging many parallax angles of a star, the measurement error of the average (root-mean-square error) cannot be smaller than the average of the errors (absolute values) of the single angles”.

"Research on Red Stars in the Hipparcos Catalogue" - by Vittorio B. Goretti (2013)

Short of denouncing ESA for outright fraud, Goretti nonetheless suggested that the scientific community should urgently address the many issues raised by ESA’s catalogues, such as their flagrant cherry-picking and evident misrepresentation of their stellar parallax data (ostensibly aimed at concealing, manipulatively, the high incidence of stars exhibiting negative parallax).

Again, under the Copernican model, negative stellar parallaxes simply cannot exist. If Earth were revolving around the Sun, all of the observed stellar parallaxes would have to be positive. So how is this negative parallax data officially explained so far? This 'scholarly' answer (courtesy of Mike Dworetsky – senior lecturer in astronomy at UCL / London — from a SpaceBanter Forum thread in December 2016) gives us a hint.

“If you have a list of parallaxes of very distant objects, so that their parallaxes are on average much smaller than your limit of detection, then the errors of parallax are distributed normally, with a bell-shaped curve plotting the likely distribution of values around a mean of nearly zero. Hence we expect there to be approximately half of those published parallaxes with values less than zero and half with values more. Negative values are unphysical, but form the part of the statistical distribution of values that happen to lie below zero when the mean is close to zero”.

In other words, someone is actually trying to tell us that since most stellar parallax angular measurements are so very minuscule (“even smaller than the optical limits of detection”), the fact that half of them are negative is just a matter of some 'Bell-shaped curve of statistical distribution'!

If this were the case, why then would ESA even go to the trouble of publishing stellar parallax figures - at all? If the published negative parallax figures are inherently useless (since they are allegedly “false negatives” imputable to the error margins of the instruments being larger than the observed parallax itself) why then should the positive parallax figures be any less useless - or any more trustworthy? Besides, isn't ESA proudly boasting to have achieved a stunning "1-milliarcsecond error margin"? None of their excuses for the existence of innumerable negative parallaxes in their catalogues makes any sense.

In later years, some geocentrists have also noticed the nonsensical negative parallaxes published by ESA. Naturally, these geocentrists cannot explain them, but being on the “other side” of the debate gives them a certain valuable perspective:

“I believe that conventional astronomical community are in open fraud because they completely ignore negative parallax readings, explaining them away as measurement errors, at the same time as they happily use positive parallax readings to ‘prove’ their theories in opposition to geocentrism. That is intellectual skulduggery of the worst kind in my view and is basically a lie. If negative parallax readings are ‘errors’ then what cause do we have to assume that positive parallax readings are not themselves also ‘errors’.”

“The Hipparcos satellite recorded that 50% of the parallax readings were negative which is not possible. In one of the biggest cover ups in scientific history the readings were ‘adjusted’ (or I would call it cooked) to make them all positive”.

— "Please provide a Geocentric diagram"- at The Thinking Atheist Forum (February 2013)

Still other researchers have pointed out that ESA’s “Tycho 1 Catalogue” actually features three distinct categories of stellar parallaxes (positive, negative and "assumed zero"), the latter category actually making up 46% - or almost half - of them all.

“Over 1 million objects are listed in the Tycho Main Catalogue, and they state: ‘The trigonometric parallax is expressed in units of milliarcsec. The estimated parallax is given for every star, even if it appears to be insignificant or negative (which may arise when the true parallax is smaller than its error). 25% have negative parallax, 29% positive parallax and 46% assumed zero parallax.”

— "Amateurs measuring parallax" - at the CosmoQuest X Forums (February 2014)

Now we are getting to the meat of the matter. The various groups of stellar parallaxes listed in ESA’s vast "Tycho 1" Main Catalogue are, in fact, distributed as follows:

Positive parallaxes : 29%

Negative parallaxes : 25%

“Assumed ZERO parallaxes” : 46%

Anyone blessed with the gift of patience and statistics should be able to verify for themselves just what Vittorio Goretti (and others) discovered. Namely, that the stellar parallaxes recorded in ESA's "Tycho 1" catalogue are indeed distributed as described above.

We shall now see that, under the TYCHOS model's configuration (and its implicit spatial perspectives), all of this would make perfect sense.

My below graphic shows not only why these three different categories of stellar parallaxes would exist; it also illustrates (conceptually) why their respective distributions - as listed in ESA's "Tycho 1" star catalogue - should be naturally expected.

As you can see, the distributions of the circa 1 million stellar parallaxes (as listed in ESA’s Tycho Main Catalogue) would seem to be perfectly congruent with the TYCHOS model’s cosmic configuration. As Earth slowly moves (from “left to right” in my above graphic) by 7018 km every six months, astronomers will measure the parallax of any given nearby star against more distant, fixed star clusters. Depending on which of the four quadrants is scanned, nearby stars will appear to drift by different amounts and directions (or not at all). In all logic, nearby stars located in the “lower quadrant” of the above graphic will exhibit positive parallax, whereas nearby stars in the “upper quadrant” will exhibit negative parallax. On the other hand, nearby stars located in the "left and right" quadrants of the above graphic will exhibit little or no parallax at all - since we are moving either away or towards them. (Note: we shall soon see that it gets rather more complicated than that, since parallax measurements will also depend on the particular annual time-window chosen to measure a given star's parallax).

As it is, the biggest question elucidated by the TYCHOS model might just be: “Why do most stars exhibit practically no parallax at all?” In fact, almost half of the stars listed in ESA’s monumental catalogue are listed as having "zero assumed parallax". Well, under the TYCHOS model’s geometry, this is something that would be fully expected - as my below graphic should further clarify:

Logically, any nearby star located in the two opposed “equinoctial quadrants” of our celestial sphere will not exhibit ANY detectable parallax for the simple reason that Earth will be either approaching or receding from them (that is, providing that the 6-month time window chosen to observe them will span between March and September - or vice versa). In the TYCHOS model, the “equinoctial quadrants” will always (at all times and epochs) be in front of or behind Earth’s direction of travel. This can be readily verified and understood by perusing the Tychosium simulator.

My next diagram should clarify just why, as previously mentioned, the whole question of stellar parallax wholly depends on the particular, annual time-window chosen to measure a given star's lateral drift against the more distant, 'fixed' stars - and thus, why so much confusion has haunted the history of stellar parallax measurements.

If two astronomers (JOE and JIM) were to measure the parallax of Sirius - JOE choosing period "A" and JIM choosing period "D" - here's what would they would (conflictingly) conclude:

JOE (choosing the March 2000 > Sept 2000 time interval) would conclude that Sirius has moved by a 'factor' of 3 (in one direction)

JIM (choosing the Sept 2000 > March 2001 time interval) would conclude that Sirius has moved by a 'factor' of 1 (in the opposite direction)

Note also that if JOE and JIM had instead chosen to measure the parallaxes of Zavijava and Kruger60, they would probably both have concluded (and actually agreed) that those two stars exhibit no parallax at all. Yet, if they had chosen any other time periods (such as B or C), they would both have detected some parallax for Zavijava and Kruger60! In fact, depending on the time frame chosen, we may envision endless combinations which, of course, will cause constant torment and head-scratching to poor JIM and JOE! Another variable which would compound their confusion would be if JIM and JOE were to be located at the opposite hemispheres of our planet (say, in Paris and in Cape Town), as their perception of "positive vs negative" parallax would be inverted...

We just saw that JIM's and JOE's observed parallaxes of star Sirius would have been conflicting (at a 3:1 ratio). Well, it so happens that, back in the days when stellar parallax detection was the most vividly debated topic among that epoch's top astronomers (e.g. Bessel, Hooke, Bradley, Struve, Huygens, Herschel, Cassini, Maskelyne, Lacaille, Lalande, et al), their first obvious choice of a star to measure was Sirius (the very brightest star in our skies). All of their measurements of the Sirius parallax were in fact conflicting (as well-documented in historical astronomy literature); but of even more interest (to the TYCHOS) is to compare the stated maxima and minima values of their discordant data: the largest parallax reported for Sirius at the time was 8"(eight arcseconds) - whereas the smallest was 2.5" arcseconds, albeit "in the wrong direction"!...

"In the early 1760s the vexing problems of parallax were tackled once more, this time by Nevil Maskelyne in England and Jerome Lalande in France. Both based their work on observations made at various times by the French observational astronomer the Abbe de Lacaille, who published in 1758, in his Fundamenta astronomiae, the observations he had made of Sirius from the Cape of Good Hope during 1751 and 1752. (...) The star in which he was especially interested was Sirius, the brightest star in the heavens. From Lacaille's observations he calculated that its annual parallax could be as much as 8", a surprisingly high value for Maskelyne to consider likely in the light of Bradley's conclusion in 1728. (...) He finished his brief "history" with some remarks about Lacaille's observations both from the Cape and from Paris. Of the observations used by Maskelyne he said: "... but these observations of Sirius only go from the Summer of 1751 to the following Winter; and there could have been some local cause which had produced in these observations the differences of 8". After thus disposing of Lacaille's Cape observations, Lalande referred to a series of observations made at Paris between the summer of 1761 and early 1762, during which time Sirius appeared to have been displaced by a more realistic 2.5"; but this displacement could not be owing to parallax because it was in the wrong direction." "Attempts to measure annual stellar parallax-Hooke to Bessel" - by Mari Elen Wyn Williams (1981)

Remarkable, isn't it? We see that 2.5" is roughly 1/3 of 8" - i.e. in good accordance with the TYCHOS' expected 3:1 variation dependent on the time-windows chosen to measure stellar parallaxes. Once more, this 3:1 ratio caused by our annual trochoidal motion (see chapter 13 and chapter 21) elucidates another puzzling aspect of astronomical observations. It is therefore no wonder why parallax measurements have caused so much confusion and perplexity for the observational astronomers of yesteryear - and continue to do so today.

NEGATIVE STELLAR PARALLAXES ARE NOT GOING AWAY

So where are we today, with regards to the spiny question of NEGATIVE stellar parallax? Has ESA perhaps finally resolved this vexing problem with their latest "GAIA" space telescope - which they now claim has a most formidable astrometric accuracy of 0.000025" arcseconds?

"Gaia is able to record simultaneously several 10000s images mapped on its focal plane. About one billion stars, amounting to ≈ 1 percent of the Milky Way stellar content, are expected to be repeatedly observed during the nominal 5-year mission, with a final astrometric accuracy of 25 µas at G = 15 mag. (1 µas = 0.001 mas = 10−6 arcsec)."

Source: "DISTANCE TO THE STARS" - Caltech.edu (2018)

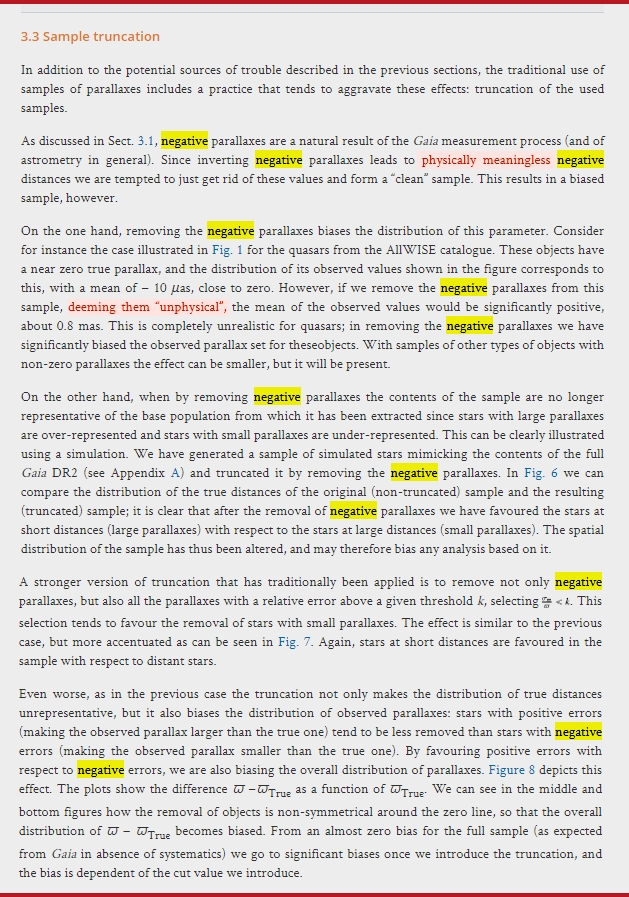

Apparently not! Here's an extract from the "GAIA DATA RELEASE 2", a report that discusses at length the issue of negative parallax - and how to 'deal with it':

"As discussed in Sect. 3.1, negative parallaxes are a natural result of the Gaia measurement process (and of astrometry in general). Since inverting negative parallaxes leads to physically meaningless negative distances we are tempted to just get rid of these values and form a “clean” sample. This results in a biased sample, however." Source: "GAIA DATA RELEASE 2" - at aanda.org (2018)

Clearly, "negative" stellar parallax is still today a major torment - even for the best-funded astronomy insitutions of this planet. One can only imagine the distress and sleepless nights this must cause to the earnest astronomers and astrophysicists employed by ESA and NASA - as they try to "justify" or "explain away" this persistent aberration which keeps producing "physically meaningless negative stellar parallaxes"!

Below is a screenshot of the above-linked "GAIA DATA RELEASE 2" report which bears testimony to the fact that the exasperating negative stellar parallax "mystery" that has haunted astronomers for the last few centuries is NOT going away:

Hopefully these poor ESA and NASA employees will, some fine day in the future, come across the TYCHOS model - and be finally relieved from their misery. In conclusion, the longstanding 'mystery' of negative stellar parallax is fully elucidated by the TYCHOS' proposed configuration of our Solar System. In the TYCHOS model, positive / negative / and zero stellar parallaxes are fully expected to be distributed at a 25% / 25% / 50% ratio - just as has been empirically observed in the last few centuries by astronomers all over the world.